Buenos Aires, Argentina 🇦🇷

Independent and self-managed project

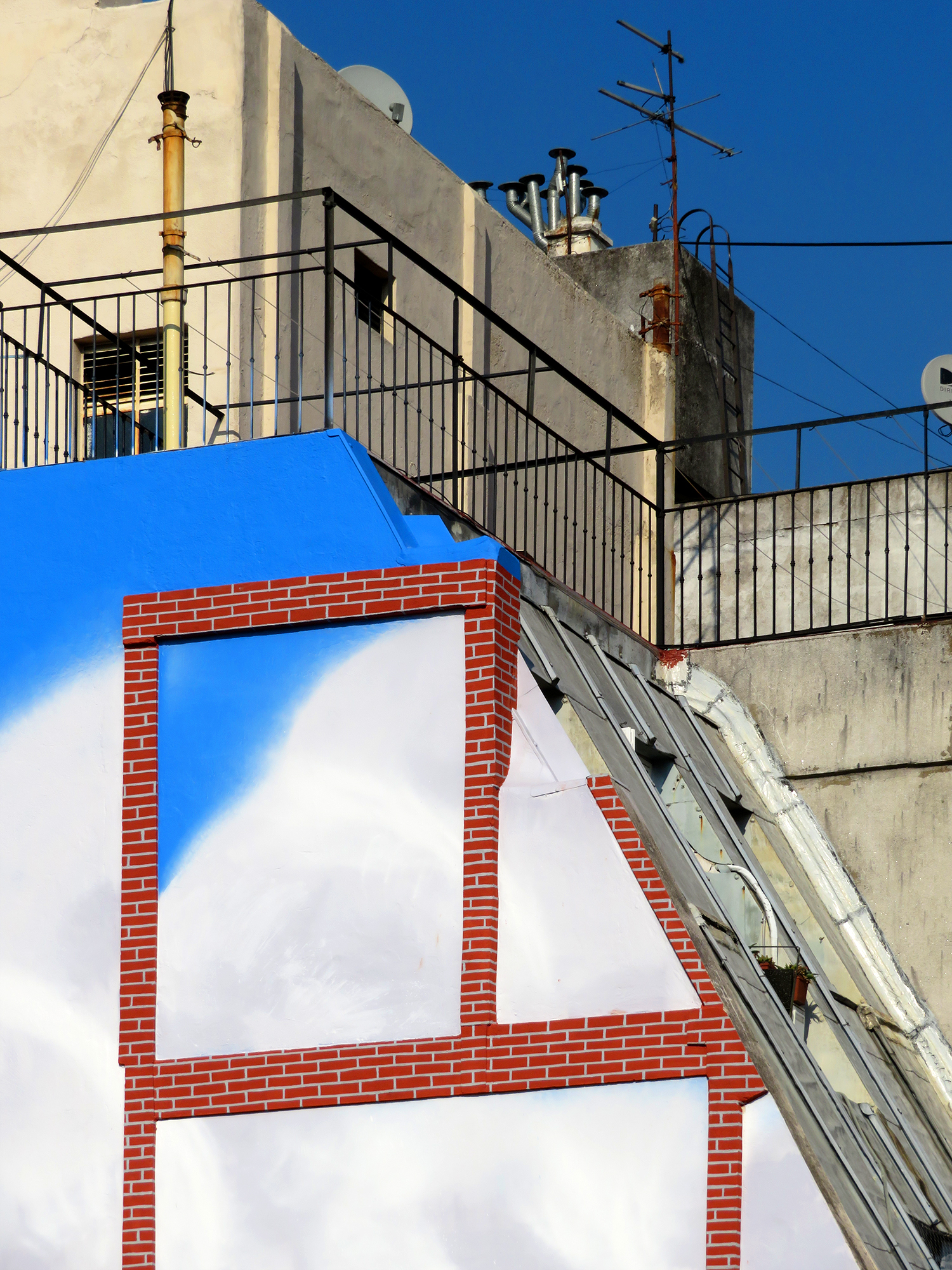

Acrylic paint and textured paint on concrete wall

15 x 35 m

2023

Text by Lupita Baliño

Photos by Santiago Ortí

Video by Orco Videos and Ether Files

This project was supported by Quimera Gallery, Pasto Gallery, Sinteplast, Impulso Cultural and Santander Foundation

•

All the keys to this corner

In the continuation of “Una gotita en suspensión”, two years after the exhibition at PASTO Galería that gave rise to this action, Jorge Pomar makes a large painting on the wall of a building in San Telmo on Avenida Independencia at the corner of Piedras.

The wall in question exhibits the marks of a building that was cut down. They are the signs of an interruption. The traces are subtle, to notice them one must have a look in love with the wall, which somehow is waiting to find its imperfections, its breaks, its cracks and its smooth parts, but above all it is a look attentive to the life in the wall, to the vestiges of the passage of time and the passage of the experience of life through the places of the city.

San Telmo has a strong hauntological quality if you will, or ghostly. It is one of the oldest areas of Buenos Aires, and the landscape with its buildings and views shows what remains, what is new, and especially what no longer exists. The neighborhood’s morphology has been changing noticeably, particularly in recent years, partly as a result of the advance of the so-called gentrification. For the people who have lived there for years, walking through this area can mean seeing in the streets, superimposed on what is there, what once was there. Because history can be thought of in some way as a holographic figurine, which is several things at the same time in a single cutout: depending on where and how you look at it you will see one image or another, or something being at the crossroads of two different things.

This dividing wall -which is now a sky in sight-, was at some point one more element in an inside, it was part of the daily life and the intimacy of the people who lived within those walls. The wall offers a story about the growth of cities, their transformations and urban planning. It is a reminder of how technological advances for life in cities somehow always generate interruptions (sometimes more silent, sometimes more visible and obvious) and operate bifurcations on a more micro and unnoticed scale: the one that occurs in the stories, in the lives of the people.

Could it be that painting the sky on the facade gives it an aura of protection? As if it were a psychomagical act to hide the fragility of our days and protect us from the action of the world: if there is a sky and no wall, it can no longer be destroyed. The brick is vulnerable to human action but the sky is unbreakable.

I think that the representation of the brick in sight is part of the repertoire of possible, virtual and synchronic images that are condensed in places. In this sense, it is interesting to insist on continuing to think about what was there and what happened with what was there. This action is a gesture of bringing back memory, at the same time as a signaling of emptiness: when we speak of spaces that are no longer there, it is really important to us to keep thinking about what was there and what happened to what was there.

When looking up, it is good to keep in mind that both the sky and the “above” are always terrains of disputed meanings. Heaven does not mean the same thing to everyone, nor is it factually the same for everyone. It is not equally accessible to all, and there are even those who are deprived of seeing it. Historically and ideologically, the sky can be only a landscape, a navigation route or the final promised land. It can be the territory of technological or commercial conquests, or the target of policies that watch over the health of those below it.

To paint a sky on a wall is to exercise a kind of playful gesture from the action of cutting and relocation that makes the facade a continuation of the sky. There is a mirage enclosed in the bricks, which can be an illusion of having the superpower to pass through walls. But to paint a sky on a wall is also to want to inaugurate a portal to the future, to the possibility of something different, more diaphanous, perhaps utopian: a city that does not withdraw gray on itself, but that opens towards the clouds, that is not heavy and impassable but light; a city where more attention can be paid to the world surrounding it all. Thus, painting a sky on a public wall becomes a poetic and political proposal: an invitation to never take it for granted.